POWER IN THE DARKNESS - TOM ROBINSON'S GREATEST HIT

Interview by MM Editor Ray Coleman

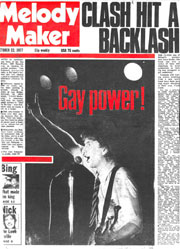

- After its controversial firing of the Sex Pistols, EMI Records may be heading for another problem. Tom Robinson, pictured right, is the label’s hottest new rock signing – and he preaches Gay Liberation wherever he goes.

- Robinson, signed by EMI six weeks ago, has been packing in ecstatic crowds to clubs all over Britain. Although his debut single, “2-4-6-8- Motorway”, is innocuous hard rock, the band’s stage anthem is “Glad To Be Gay.” And Robinson says he wants it out as a single.

- EMI, who foresee no furore over their signing because they believe “Tom has taste,” say they have no plans to censor such a track, but no release has yet been planned.

- Meanwhile, the Robinson band continues its successful trek of the

clubs, and is a red-hot favourite with London crowds at the 100 Club

and Marquee – where Tom was photographed by Barry Plummer.

The last I saw of Tom Robinson that night in Liverpool, he was bathed

in sweat, downing a bottle of lager, and peeping nervously out of the

corner of his beady left eye at two policemen who were paying a routine

call on Eric’s club. Robinson looked bothered. His band had finished

its performance ten minutes before the police arrived. It had been hard,

winning over this crowd of dubious Merseysiders, for Tom’s songs

show a burning predilection for protest. Talking openly and challengingly

to the crowd about his homosexuality, Robinson also distributes pamphlets

at his concerts, publicising such causes as the National Abortion Campaign,

Gay Liberation, the Free Prisoner George Ince Campaign and Rock Against

Racism.

If it’s a crowd that just wants to boogie, he could be in trouble,

for Robinson demands that people stand back and listen to his message.

Tonight, it had been uphill. But about three-quarters of the way through

his set, he connected. Liverpool loved the band. Robinson was elated as

he stood around chattering all those usual after-the-show withdrawal symptoms

to anyone who would listen. “Every gig outta London’s like

your first ever,” he was saying . . . and then the police arrived.

“What’s up,” he whispered. His voice sank. Nothing was

up. The police were doing a routine check at the club just as they do

on many establishments the breadth of the country. All the same, Robinson

became perceptibly jittery.

He looked at me, glanced at the cops again, then vanished, lager bottle

still in hand. The police went away and we all continued drinking. I’ve

not seen Robinson since. His instant exit at the sight of the law seemed

a perfect example of immediate polarisation of rock and the law, handsomely

portrayed in Robinson’s tirades which are fast becoming anthems

for embittered sections of society.

Robinson is a custom-built 1977 rock star, utterly committed and striking

no poses as he makes speeches from the stage against the National Front,

attends marches and demonstrations such as the recent Lewisham fracas,

and writing venomous lyrics as relevant to minority groups in the Seventies

as were Pete Townshend’s to his Sixties audience. Lest you should

run away with the idea that here we have a Left Wing agitator hell-bent

on merely using rock as apolitical weapon, it must be said right at the

outset that there’s a fundamental strength that sets him aside from

vacuous sloganeering – Robinson’s band is sheer dynamite,

pounding out good, tight, slashing rock that comes alive in a sweaty club.

Above all things, he says, he’s a musician. But being gay puts him

in what he regards as a persecuted minority. Better to sing about that,

he thinks, than about Kansas City or the boulevards of Paris. So Tom Robinson

is preaching for the people whom he thinks need a campaigner. As the title

of one of his popular songs has it, “You’d Better Decide Which

Side You’re On.” For Robinson and his band right now, it’s

a fine balancing act because he recently signed to the conservative EMI

label for an estimated £53,000 advance on royalties over five albums.

“Very strange feeling,” says the highly articulate Robinson,

as he tackled a steak in a Liverpool Berni Inn. “Six weeks ago I

hadn’t a penny – and a meal consisted of a 9p packet of soup

from Sainsbury’s.”

Robinson believes that the one thing that separates him from many hundreds

of better musicians is his single-mindedness. A fierce determination gripped

him at 3 o’clock in the morning on October 12, 1976. He knows the

time and date well, because he is a painstaking person, and he wrote down

what happened. He jumped up in bed, realised that the band he was then

with was not going to make it big, and vowed to get out and form his own

unit. His band was Café Society, an acoustic trio. They had done

moderately well playing London clubs and also going out on concerts as

support act to such top-liners as the Kinks, Leo Sayer and Barclay James

Harvest. They had been going for three-and-a-half years, though, and Robinson

was, to put it mildly, restless.

“I looked around and saw the Sex Pistols exploding all over the

country, the Clash tearing the place apart, and here was I sitting in

my bed-sit kidding myself. I knew I was never going to make it as I was.

Having told myself that, I went back into a really calm sleep because

I knew what I had to do, even though it would mean stabbing some good

friends in the back.” This he prepared to do. Next day, he told

the other members of the group he was leaving, warned the record company

by post that he wanted out, and “immediately went round all my old

contacts and started blagging gigs for a group I didn’t have.”

He put an advert in the Melody Maker, seeking “musicians who want

to be in on some amazing scenes this year . . . dynamite drummer and rock-solid

bassist for 70’s band gigging Nashville, Golden Lion, Hope and Anchor.

No bread.” He had no such gigs in sight but was oozing confidence.

The result now is his current line-up: Danny Kustow, a rich-toned, blistering

and sympathetic lead guitarist; Mark Amber, a busy keyboardist who provides

the Tom Robinson Band with its instrumental density; Brian “The

Dolphin” Taylor, a boisterous drummer; and Tom on bass guitar. They

had been together five months when, six weeks ago, the record companies

started to sniff a winner.

After building up the kind of feverish following in the clubs that can

never be hyped, they started packing in capacity crowds at such London

venues as the Brecknock, the Nashville, the 100 Club, Dingwalls, and the

Marquee. Things have moved very quickly. Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant

and several other musicians went to see them, and ere long the general

buzz reached record companies. The might EMI beat Jet Records to the signing,

and the band’s debut single “2-4-6-8 Motorway,” is doing

well. The Tom Robinson Band looks unstoppable; there can be no turning

back for a band that combines razor-sharp music with ironclad commitment.

For while the music is splendid in this band, it’s true to say there’s

no shortage of fine rock music around. What separates Robinson from the

mob is his open stance as a homosexual, and his campaigning for certain

rights which have brought him into, er, dispute with the National Front.

On stage, he’s a charismatic, commanding figure who positively leads

his band and takes the lead vocals with either heavy aggression or disarming

smiles, depending on the song. It’s his toothy smile that’s

engaging. Off stage, he’s an interesting conversationalist, a bit

of a chatterbox, a stickler for detail.

He’s as fascinated as you or me by his appeal, as a self-confessed

gay rock singer. But asked why he believed heterosexual girls would go

to his shows, allowing that they traditionally went to shows where they

“liked” the guys on stage, Robinson thought long and hard.

“The front row is all girls, nearly every gig. Hmmm. I think the

great thing for young women coming to our gigs, and the reason they enjoy

it, is because they feel they’re not going to get some kind of heavy

trip laid on them. They can just enjoy the music for its own sake, talk

to somebody whether it’s a guy or a woman, and there’s no

great big deal going down. The guy isn’t about to get all heavy

and say: ‘Oy, do you wanna come back to my place, darlin’?

They feel unthreatened. And at a lot of gigs you can’t, if you’re

an unaccompanied woman. So that’s good.”

He decided to stand partly on his gay ticket when he redirected his career

at the end of last year. His old band Café Society had been signed

to Kink Records, run by Ray Davies. The Kinks star had seen Café

Society at London’s Troubadour, where they played each Tuesday throughout

1973 and 1974. The contact with Davies had been made through John McCoy,

a Teesside promoter who managed singer Claire Hammill. Robinson was a

fan of Davies, and despite what happened later between them, he pays a

glowing tribute to Ray: “He was the first person anywhere in the

music industry to take an interest in me personally, and he really gave

us some ideas, sorting though the themes I had in my head and tips on

how to perform everything. He gave me my first break and if it hadn’t

been for him and Café Society and Konk, I wouldn’t have known

how to approach the Tom Robinson Band at all.”

Davies it was who taught Robinson the machinery and politics of the music

industry. But later, when Tom wanted out and said he intended to form

his own band, Davies and he became involved in a bitter, protracted legal

dispute over contracts and publishing of songs; the battle is still very

hot and may drag on for a long time. No matter, Robinson has lots of time

for Davies as one of his heroes, and gets quite emotional when he recalls

Ray playing “Waterloo Sunset” alone at the Troubadour, with

other friends, including Alexis Korner, sitting in the small congregation.

“Magic, pure magic. The man is one of the few real geniuses of British

rock ‘n’ roll. Make that rock. Shakin’ Stevens and the

Sunsets are the guvnors of rock ‘n’ roll in Britain. Rock

‘n’ roll and rock – big difference.”

Davies advised Robinson not to be overt about his gay persuasions. “Ray

would say ‘you should keep people guessing. It’s better on

stage that way,’” says Tom. But came the winter of ’76,

and Robinson could take no more of the shilly shallying which being in

another band forced on him. Actively involved by now in Gay Lib causes,

he wrote this song “Sing If You’re Glad To Be Gay”.

<Glad To Be Gay Song lyrics>

It wasn’t, he avers, written out of bravado, and certainly not

to grab headlines; he couldn’t think of a more difficult pitch to

defend in a quest for popular appeal. And he could certainly have made

a success out of music without using this personalised theme. It was a

song conceived partly out of irritation at the “keep them guessing”

technique employed by many other big rock stars.

Robinson sees his statements as the final instalment in a direct line

of descent from the Camp Rock period of five years ago. On January 15,

1972 (Tom remembers the date well), David Bowie was front-paged by the

Melody Maker at the time of his “Hunky Dory” album. Inside,

under the headline “Oh, You Pretty Thing,” the matter of gayness

was discussed in some detail. It all made a resounding impression on Robinson.

“There’s this slight attitude about the way Bowie talked,

that glint in his eyes . . . but you know Bowie got the Camp Rock posture

from Lou Reed and he in turn got it from Ray Davies. Surely everybody

remembers ‘See My Friend.’ By the time Ray hit the States

in ’66 he was known, over there at least, to be a Camp performer,

showing his backside to the audience and saying: ‘Do you like it?

It’s the nicest one in show business.’ Ray used to say it

was a careful plan to tease the audience into unity, and he still says

I ought to be a little more subtle, keep them guessing, because they find

that more interesting if they’re not quite sure. I didn’t

choose to play that particular game, but that was Ray’s advice.”

But now, it’s 1977 and for these brutal times, Robinson says nothing

but the truth will do. “The time’s come for people to stop

beating about the bush, whatever they’re into in life. Either you

put up or shut up. For me personally, the hint of it was enough to please

me, as a self-oppressed, self-hating, lonely, acne-riddled youngster as

I was at the time . . . to actually hear a guy singing songs which you

suspect might be about another guy . . . you know, for the first time

in your life, that song could be about you. I don’t know if you

can understand this, but up until then, all the other songs had been about

somebody else, and suddenly I’m thinking; ‘Hey, this is very

nice, this is how I feel.’”

Before Bowie, the only other song, which mirrored how he felt, was John

Lennon’s “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away.”

Robinson recites the words to that verbatim, hanging on every word, positive

that they were written by a spirit who understood. Today, Robinson’s

words plead for gay women as well as men; “I feel very passionately

that everybody has the right to do what they bloody well want with their

own body if nobody else is being hurt. However, I want it on record that

I was with a woman the other night, and it would be a shame if in singing

out about the rights of gay women and men I would be then regarded as

a traitor if I then went to bed with whoever I wanted to.”

“The words they call us, some even shout out to us at gigs, y’know

– they hurt. But when people say; are you gay, queer, a homo, a

pansy, a faggot, a poofter, or any of these nice little names they’ve

got – I say yeah, what’s it to you? But as far as Joe Public

is concerned, whatever else you do, if you’re interested in other

guys, or if you’re a woman with a woman friend, you’re a queer.

Still, we must get used to it, I fear – certainly to call ourselves

bi-sexual is a cop-out. Some of the top musicians in rock make me laugh.”

As far as the rest of his band was concerned, he said he did not know

about their personal habits. “As far as I know, I just think none

of them is – you know, I took them on as musicians. Funny thing,

everybody is taken to be heterosexual unless proved otherwise.”

“It wasn’t a prerequisite for anybody joining the band –

I wanted good musicians. I mean Joni Mitchell presumably doesn’t

require people who apply for a job in her band to be a woman." It

would be easy to shout; “Publicity stunt” at Robinson, and

he’s aware of the fact. “People pre-judge us by our publicity,

and some have the horrors about coming to see us. It’s been suggested

to me that I actually wrote political lyrics to some of the songs, or

actually owned up to being gay, to simply promote the band, make more

people come to our gigs, and get sensationalist coverage by the media.

My God, we’d have had an easier ride if I hadn’t. People STAY

AWAY from gigs on the assumption that we are a gay rock band and they’ll

be standing in the middle of a bunch of screaming faggots. Incidentally

– so what if they are? Screaming faggots are extremely nice people!”

“Straight people think ‘I don’t want to go to these

gigs to mix with those kind of people.’ They think if there’s

a homosexual lurking in the band, it’s going to be a certain kind

of scene. But surely they can see that it’s better for me to own

up than keep it quiet? The other preconception is that they’re going

to be lectured, preached at, taught didactic songs. This is not the ultimate

idea. I write some lyrics for the band, which is how some songs have that

flavour, but basically we’re all into it because it’s a rock

band, and it has to be the music that people enjoy before we can do anything

else with it. If it doesn’t work on the basis of good, enjoyable

rock ‘n’ roll, it doesn’t mean a thing. I’ve been

a professional musician for three years. I would still be playing music,

even if I stopped being a professional tomorrow. Music first. I’d

be a hypocrite if I set out myself as a social reformer or a revolutionary.”

It’s difficult to accept this line from Robinson, however, because

the emblem of the band, used in their stickers and badges and adorning

the pamphlets handed out at their performances, is a clenched fist. If

that doesn’t spell militancy, I said, what was it all about? If

rock ‘n’ roll was the medium, there was also a message . .

. “Yes, but the medium IS the message, in a way. Maybe the motivation

is wrong anyway, but listen, if you are a songwriter working in a rock

band and you enjoy yourself playing music, and you’re making music

people can dance to, and they can enjoy for their own sake, then within

that the lyrics do have to be ABOUT something. May as well be about what

I believe. If people like them and can relate to them, even better. If

they can’t and don’t show up at the gigs, I’ll soon

know that what I’m saying in my songs is unpalatable in commercial

terms.” That, one suspects, would be untenable for him.

The more one talks to Robinson and observes him, the clearer he emerges

as a Machiavellian character whose guiding light is merely a chronic determination

to be famous, and a liberator of the oppressed. Certainly he’s touched

upon a nerve for thousands of Leftist causes, which is surely the very

stuff of rock ‘n’ roll. But it’s one thing to feel that

way – and quite another game to convert it to fine music, a happening,

which sends you from his shows in a buoyant mood. At London’s 100

Club two weeks ago, the queues were forming an hour before the gig began,

and so packed was the crowd for the band’s electric performance

that it was not possible to move around once a position had been staked

for the night. Sardinesville.

At the Nag’s Head, High Wycombe, they were, apocryphally speaking,

clinging to the rafters, and at Eric’s Club, Liverpool, the traditionally

cool provincial attitude to Robinson’s directness was well and truly

defeated so that by the end an encore was earned and another victory scored.

“You come away from a punk concert these days and you feel HATE,

KILL, SMASH SOMETHING. You feel bigoted, very often,” Robinson says.

‘You come away from a Wailers concert and you jump in the air, you

go WHOOOOOH! Clap hands, click your heels, jump around and feel really

happy. That’s what I want people to feel when they come away from

our gigs – uplifted, positive, going up, achieving something, united

together. That’s what music has got to be doing, and I would hope

people could find some kind of strength and solidarity. That’s the

word – people should get solidarity from the TRB, rather than coming

to find a political lecture.”

Nevertheless, the opening song by the band on most gigs is a classic commentary

in the tub-thumping manner of protest songs. “Winter Of ‘79”

mirrors precisely the doom Robinson sees ahead as Britain lurches towards

a middle class backlash:

<Winter Of ’79 lyrics>

This song epitomises the desperation that’s implanted deep into

the recesses of Robinson’s mind, and which it takes a long time

to reach when talking to him. If he could ease up a tiny fraction of the

intolerance, hatred and prejudice in the world, he said, it would be worth

it. Above all, he was determined to speak as a 1977 person. “Conditions

are getting worse, and when this happens, the hatred, distrust and prejudice

build up. I’d originally like to have been a Liberal, but there

are no Liberals in ’77. It’s make-your-mind-op time, because

it’s becoming increasingly true for both extremes that if you don’t

stand on one side or the other, you’ll get well and truly caught

in the cross-fire.”

He’s 27 and, naturally, a Guardian reader. Born and schooled in

Cambridge. His father, a schoolteacher’s son from Lincolnshire,

plays cello. Tom once played clarinet in a dance band, and early in his

life was taught piano, but he renounced this as the stage instrument in

his current career because: “If you notice Keith Emerson or Elton

John, they can’t move from the keyboards, whereas some of their

songs demand some physical movement. Guitar appealed because you can move

around the stage when you’re playing and singing. Don’t like

static instruments. Same with drums – too restricting.” He

attended a co-educational Quaker boarding school, and his father, who

is heavily into Bach, believes that most pop is useless and that “anything

after 1850 stinks, unless it’s baroque,” according to Tom.

Young Robinson was forced to take piano lessons from age 4 to 13, but

made poor progress. Eventually, he was bought a guitar, and drifted towards

Cambridge area pop groups, the Lost Souls, the Ravens, the Nomads. After

boarding school and with a string of A levels and O levels he came to

London at 20 and went to the Musician’s Union seeking a job as a

bass guitarist. Not a hope they said – but they pointed him to a

clerical job at the classical music publisher J.B. Cramer, £19 a

week, 9.30 until 5.30, and the routine of it pleased him. “I’d

go back like a shot. At 5.30 you could shut the door and your work was

behind you and you could then go and enjoy whatever pleasure you wanted

to, and that’s great.”

Having worked with others under the corporate name of Café Society,

he faced the problem when launching his own band of whether to assert

his own name, risking the possible future wrath of the others seeking

a coalition, or “deciding on some other absurd name like the Fuzzbombers

or whatever.” Typically, Robinson’s single-mindedness won

the day. Interestingly, the factor that decided him to promote his own

name was practicality, “Because I’d been in the moderately

successful Café Society, I had a very, very minor name of my own.

So if by putting Tom Robinson upfront it would mean there would be an

extra five people at the gigs, it was worth doing it. And after a couple

of months, who’d be stupid enough to change it? Democratic? I’ll

say. Because it’s me who’s the front man, nobody’s trying

to prove anything. There’s no problem. We all have an ego, but we’re

all sensible enough to realise that all we ever do is for the good of

the band.”

“The thing I live for, and have done ever since the TRB was formed,

is performing on stage – for that one hour ‘fix’ per

night. And I live the other 23 for that, so that making records and all

the rest of it is just a means to be able to improve conditions, for more

people, have more fun, and do a better show. It’s a means to carrying

on for me. I’m absolutely determined and committed to improving

the band – that’s what separates our success now from what

was achieved by my old band. And you know, if EMI threw us off the label

tomorrow, I wouldn’t even break stride.”

The EMI situation is, at first sight, delicate. The company’s last

hugely controversial act, the Sex Pistols, were paid off so that EMI did

not have the embarrassment of dealing with a burgeoning career of what

people Upstairs In The Boardroom would regard as morally questionable.

This time, with the Robinson position as uncompromising and potentially

as lethally controversial for EMI as the Pistols, there seems unanimity

because it is a band that’s seen to put music above message. Also,

EMI bosses say that Robinson has “taste” when discussing his

gay ideals. Bob Mercer, director of marketing and repertoire at EMI, sees

few problems ahead, mainly because he regards Tom as “a very intelligent

and controlled person. There’s an anti-Establishment attitude from

most bands,” says Mercer. “Tom Robinson has had a particular

stance in connection with Gay Liberation, but EMI does not regard itself

as a censorship outfit.” What were the chances of confrontation

between artist and record company over such areas as militant lyrics or

album cover designs?

And was EMI aware that in Robinson there was a prickly character that

would stop at nothing? “We often meet that attitude from musicians,”

Mercer answered. “It’s always easier, not harder, to deal

with someone like Tom Robinson, whose perception is profound. The power

of reason wins through if you are not dealing with an impractical mind.

He’s very perceptive, understands the music business, leads a great

band, and EMI is convinced it will be one of the biggest successes in

the land.” America beckons, too, and it’s certain that the

gay publicity will be a powerful piece of ammunition in that country.

The massed band of EMI went after the band at the Brecknock pub in Camden

Town six weeks ago. Early reconnaissance had been carried out by A&R

men Nick Mobbs and John Darnley, but Mercer led the final swooping force

of between 20 and 30 at the Brecknock, and he recalls that the whole party

“went absolutely crazy” with determination to sign the band

against all contestants. It is a fact that while other companies had offered

more immediate cash to Robinson, he and the band opted for EMI because

they fancied “their machine.” After that pub gig, Mercer and

the hit team took the band for a meal, talked into the early hours, and

they signed next day.

Three weeks ago, Robinson attended an EMI regional sales conference in

Manchester and impressed all with his intimate knowledge of how the record

industry functions. Asked about such hard-headed pragmatism, he told me

coolly: “if you want to have more people than you can actually play

to in one place at one time, to hear what you’re doing and listen

to your music and your views, then you have to make records. If you’re

going to make records, you may as well do so with the best company you

can get hold of, EMI, and once you’ve reached that position, you

must do it wholeheartedly rather than mess around.”

What of his controversial possibilities and the prospect of friction with

the company that axed the Sex Pistols? “Well, yeah, I guess that

firing thing could happen to me but then I see now how silly they were

with the Pistols. Really, the point is that EMI is a public company and

therefore vulnerable to interference from people who don’t understand

musicians. But anyway, nothing’s gonna get in the way of this band.

EMI offered me terms that were well above the normal contract, but if

that goes wrong, I won’t let it stop me. The band is on course,

so to speak. I’ll tell you what I’ve told everyone all along

the line. I’m a musician and I like the applause. I’m in this

thing for the ego trip; I don’t want anyone coming back to me later

and saying I lied. You know, you read about the Clash and the Pistols

denying they want to be pop stars, and it doesn’t make sense. They

can come on as nasty as they like, but they want to be pop stars, and

I don’t see why they should be forced into a position where they

say the reverse.”

Talking of the punks, or the new wavers, Robinson didn’t seem to

care with whom he was bracketed. But one of his most potent songs was

clearly aligned with the kids on the streets:

<Up Against The Wall lyrics>

You get the distinct feeling that if there’s one person with whom

he parallels himself, it’s Pete Townshend. The mere mention of The

Who star’s name sent Robinson into paroxysms of admiration. “Nobody

can touch him, for what he’s achieved for rock music in the world

generally, and for the way he was talking about politics generally back

in 1970 and 1971. It pre-dates everything we’ve got now. A guy like

Townshend is, to me, like a colossus in rock, more important than anyone.

And because of the magnitude of his achievements, it’s unfair to

compare him with other people – like Charles Mingus said of Duke

Ellington, ‘this guy should be banned from the opinion polls!’

Mingus said something about first place being set aside for Ellington

year after year, and then let’s talk about the rest of us. I feel

that way about Townshend. You judge it from number two downwards after

him. And out of all those Sixties bands, the Who’s the only one

that’s still going with the same amount of commitment beneath them

that they had early on. Others have become a caricature of themselves,

a charade. Too much negativity going down.”

He’s warm towards jazz, like Miles Davis, but cites Manfred Mann’s

“Five Faces Of Manfred” album as one of his all-time favourites.

Richard Thompson is named as “one of the absolute greats of British

song writing.” To contrast with the stern aspect of his lyrics,

there is the Cockney accent, perhaps a heritage from Ray Davies, which

Robinson carries off quite amusingly on stage. There’s an ode to

a “brother” called “Martin” which is a simple

song of friendship, but the tongue-in-cheek joyride, which clinches his

sense of the ridiculous, is a song immortalising the Ford Cortina:

<Grey Cortina lyrics>

He is in love with the whole kitsch trip of such a model, and after dinner

at the Liverpool Berni Inn, he said a Mark II Cortina to whisk us away

would have made the fantasy complete for him. “Do you know, my contact

in the motor trade tells me that a J registration silver fox 1600E will

fetch its weight in gold in the open market? A client of his bought one

from somebody for £1,500 last week. It’s like I say –

the silver-grey ones go faster.” Nodding dogs on the rear shelf

and fur trim would be essential for him, of course . . . ah, the luxury,

the lunacy.

Robinson smiles at the thought, but it’s the smile of an escapist.

He’s going to score heavily over the ephemeral appeal of hundreds

of other bands next year, because his music is rock hard, and his commitment

is very real. But like his mentor Ray Davies, he’s the classic character

portrayed in Smokey Robinson’s “Tears Of A Clown.” “As

close as I am to any guys on this earth,” the heavily emotional

Robinson said finally, “I’m close to the guys in my band.

Yet . . . I’m not really close to any human being on this earth.

I’m very lonely. This band’s my life, and I don’t find

time for anybody or anything else. It’s cost me all my friendships,

this determination thing . . . and my worst fear is that if the band’s

successful, having a nervous breakdown or something, because you can get

so isolated and removed from reality. I’ve watched people, and you

have to be so on the ball all the time, just trying to keep yourself away

from that abyss.” Was it worth it? He didn’t flinch from replying,

with that quicksilver, steely outer wall of confidence:

“Of course. You see, I suddenly shot out of bed from my sleep, last

October 12th...”

RAY COLEMAN